German payment processing company Wirecard is currently falling apart under a criminal fraud investigation after 1.9 billion euros went missing. What is lesser known, is that the company, which got its start by processing gambling and porn payments, also apparently ran psychological warfare campaigns to silence whitleblowers.

In today’s episode of The Private Citizen we talk about the German tech industry darling Wirecard, a payment processing company that has been all over the news for all the wrong reasons lately. Aside from having lost billions of euros and being accused of fraud, they’ve also spearheaded a new way to gaslight and silence critics.

The Rise and Fall of Wirecard

Wirecard was once one of the biggest stars of the German tech industry. It started as a humble secure payment provider back in 1999 – before the Dotcom Bubble burst – and back in the day mostly provided its services to online gambling and porn sites.

In recent years, Wirecard has exhibited a meteoric rise into the ranks of the German blue chip stock market index DAX (Deutscher Aktienindex). These days, Wirecard is a full financial services provider and a bank. It is also under criminal investigation for fraud as of Monday, because €1.9 billion in cash went missing from its books.

The Case of the Missing 1.9 Billion Euros

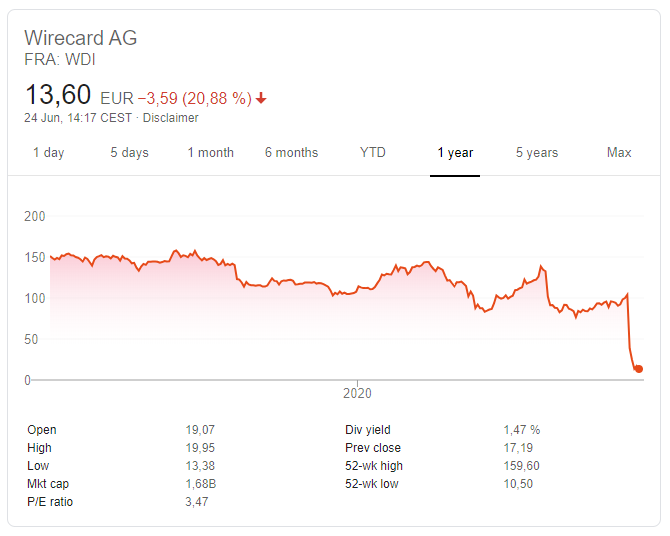

Wirecard is now under criminal investigation by German authorities and its stock is in free fall:

Wirecard stock price earlier today (Source: Google)

Here’s a report from The Financial Times:

Wirecard has for the first time acknowledged the potential scale of a multiyear accounting fraud, as the German fintech group warned that €1.9bn of cash on its balance sheet probably does “not exist”. The payments company said it had previously mischaracterised its biggest source of profits and that it was now trying to work out “whether, in which manner and to what extent such business has actually been conducted for the benefit of the company”. It withdrew its most recent financial results and said other years' accounts may be inaccurate.

This is an unprecedented situation for a DAX company and onlookers are positive that it will cause major and long lasting damage to the trustworthiness of all German companies and also the market establishment in general. Because the regulators did not do their job at all.

As Wirecard’s shares resumed their precipitous fall – down 33 per cent on Monday and more than 80 per cent since the collapse began on Thursday – the German establishment began its own reckoning. Felix Hufeld, the president of German financial watchdog BaFin, said the Wirecard scandal was “a complete disaster” and “a shame” for Germany – a market that “should be governed by quality and reliability”. But he defended a two-month short-selling ban the regulator imposed last year after Wirecard’s Asia headquarters were raided by Singapore police.

So what happened?

Meanwhile, Wirecard was trying to salvage its payments processing business, licensed by Visa and Mastercard and responsible for tens of billions of euros in annual transaction volume, having called in restructuring experts during a weekend of negotiations with lenders.

At the centre of the affair is Wirecard’s so-called “third-party acquiring” business. The group is an acquirer in Europe, meaning it handles credit card payments for businesses. It had also claimed to outsource some payment processing to third parties. For the past 18 months the Financial Times has reported whistleblower allegations of accounting fraud related to such third-party business. In October the FT published documents that indicated clients listed in documents prepared for auditor EY did not exist. A KPMG special audit was unable to verify the arrangements were genuine. Between 2016 and 2018, roughly half of Wirecard’s sales and “the lion’s share of its profits” were attributed to such third-party acquiring, according to KPMG’s report, published in April, and documents seen by the FT.

Moody’s, which downgraded Wirecard to junk last week, on Monday withdrew its credit rating, saying it had “insufficient or otherwise inadequate information to support the maintenance of the ratings”.

Wirecard customers include Aldi Süd, Fedex, KLM, Ikea and the Asian Uber competitor Grab which has now cancelled all its dealings with the German company.

Criminal Investigation Launched

Yesterday, the company’s CEO was arrested. He had just stepped down a few days ago.

Wirecard’s former chief executive Markus Braun has been arrested on suspicion of false accounting and market manipulation, Munich prosecutors said on Tuesday morning. The prosecutors are accusing Mr Braun of artificially inflating Wirecard’s balance sheet and the company’s revenue in an attempt to make the company look more attractive for investors and clients. The prosecutors suspect that Mr Braun did this in conjunction with others. A spokeswoman for the Munich prosecutors’ office told the Financial Times that the company’s former management board was under investigation.

Mr Braun reported himself to Munich prosecutors on Monday evening after a judge issued an arrest warrant against the 50-year-old who had been at the helm of the formerly high-flying German fintech since 2002 until he resigned last Friday.

Braun sold a lot of his Wirecard stock before he turned himself in. He’s now been released after paying 5 million euros in bail.

Meanwhile, ex-Wirecard board member Jan Marsalek, who was fired in the wake of the scandal, is on the run, reportedly in the Phillipines  . According to Der Spiegel prosecutors there are investigating Wirecard. The company had claimed to have business there and the €1.9 billion were supposedly parket at banks in the country, even though the banks deny Wirecard was ever a customer. The government says it doesn’t know if Wirecard ever did business in the country.

. According to Der Spiegel prosecutors there are investigating Wirecard. The company had claimed to have business there and the €1.9 billion were supposedly parket at banks in the country, even though the banks deny Wirecard was ever a customer. The government says it doesn’t know if Wirecard ever did business in the country.

Der Spiegel reports immigration officials in the Phillipines had found “something weird” in Marsalek’s immigration records but wouldn’t specify what that was. Marsalek was in the country from 3 to 5 March. Marsalek was Braun’s second in command and responsible for the company’s business in Asia.

German Regulators Under Fire

Instead of investigating a company that was being reported to them again and again for potentially shady business practices, German regulators did the opposite: They blamed short sellers and even journalists.

Ten days after police raided Wirecard’s Singapore office in February 2019 over allegations of accounting fraud, Germany’s financial regulator made its own move. BaFin banned investors from betting against Wirecard shares for two months, the first such restriction on an individual company in German stock market history. That was quickly followed by a criminal complaint against two Financial Times journalists who had reported the whistleblower allegations about the payments company. Less than 18 months later, it is German regulators who are coming under fire for failing to investigate what increasingly appears one of the country’s worst ever accounting scandals. Wirecard shares have crashed more than 80 per cent in recent days as the company acknowledged the potential scale of a multiyear fraud.

“The Wirecard scandal did not come out of the blue,” said Florian Toncar, a member of parliament for the business-friendly FDP. “It’s a mystery to me why the finance minister and BaFin did not shed light on the matter much earlier.” There is no single reason for the failings of Germany’s regulatory apparatus, according to academics and the handful of politicians who over the past year became alarmed at the gravity of the problems emerging at Munich-based Wirecard. They instead point to a corporate culture historically wary of foreign speculators, a refusal to doubt what appeared a rare German tech champion and, more specifically, the inability of Germany’s regulatory system to deal with a payments company.

Wow. And now they are slowly waking up. But only after a private sector auditor found massive problems.

“My impression was for a long time that Wirecard was seen as this delicate homegrown plant that needed to be protected,” said Fabio De Masi, a Berlin lawmaker with the leftwing Die Linke party and one of the few politicians to take an interest in the Wirecard scandal early on. Anyone asking awkward questions about its business “was seen as trying to run down Germany and its finance sector”, he added. That attitude changed this week, and even BaFin was moved to issue a mea culpa. Felix Hufeld, its president, told attendees of a conference on Monday that “a whole range of private and public entities including my own have not been effective enough” at preventing the “complete disaster” at Wirecard.

BaFin’s inability to police the space of payment service providers echos problems with PayPal that I’ve been talking about for years. In Germany, banks are highly regulated and subject to a lot of consumer protection laws. Internet payment processing companies, which in a lot of respects (especially from the point of view of the consumer) fulfill many of the same roles, aren’t beholden to the same standards, though, because they are deemed tech companies. When in effect they are also consumer banks.

Gerhard Schick, a former Green MP and now head of Finance Watch Germany, a pro-consumer lobby group, said that part of BaFin’s inertia over Wirecard stemmed from an institutional inability to carve out its role in a fluid and complex environment. “Wirecard is yet another example showing that BaFin is systematically failing to cope with complex situations where it does not have a clearly defined legal remit but needs to define its own role,” said Mr Schick, who describes the watchdog as “too formalistic and timid”.

A limited legal remit means that, unlike its counterparts in many countries, BaFin lacks the power of a criminal prosecutor and has limited authority to investigate potential accounting manipulations. Moreover, it has traditionally been dominated by lawyers who take a very narrow view on its role. In practice that meant Wirecard was treated as a technology company rather than a financial services provider, putting the holding company outside BaFin’s direct oversight even as it regulated Wirecard Bank. “It is unacceptable that a big payments service provider enters the Dax, and nobody at the upper echelon at BaFin is asking the question how it is supervised," said Mr Schick.

Psychological Warfare against Whistleblowers

Now, why am I talking about all of this on a privacy-focused podcast? Because NPR took the renewed interest in Wirecard as an opportunity to release an episode of their Invisibilia podcast that they had prepared earlier and which deals with the fate of a short seller who ran afoul of the newly-troubled company. The episode is based, in parts, on findings of the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab that were published at the beginning of June.

It is not immediately clear why NPR choose to hold on to their podcast episode for so long.

Material prepared to discredit whitleblowers, allegedly by BellTroX InfoTech Services (Source: University of Toronto)

The Citizen Lab report and NPR’s podcast detail extreme invasion of privacy, psychological warfare and hacking attacks that shady operators perpetrated against detractors of Wirecard. These operators are thought to have been from Indian company BellTroX InfoTech Services, apparently a hack-for-hire outfit.

Researchers discovered almost 28,000 web pages created by hackers for personalised “spear phishing” attacks designed to steal passwords, according to a report published on Tuesday by Citizen Lab, part of the University of Toronto’s Munk School. The report said a large cluster of targeted individuals and organisations were involved in environmental issues and had campaigned against ExxonMobil, the US oil producer. They included the Rockefeller Family Fund, the Climate Investigations Center, Greenpeace, the Conservation Law Foundation and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“The growth of a hacking-for-hire industry may be fuelled by the increasing normalisation of other forms of commercialised cyber offensive activity, from digital surveillance to “hacking back”, whether marketed to private individuals, governments or the private sector,” the report said. A prominent example was the targeting of “hedge funds, short sellers, journalists and investigators working on topics related to accounting irregularities at German payment processor Wirecard”.

Citizen Lab said that in the case of Wirecard critics, “some individuals were targeted almost daily for months, and continued to receive messages for years”. The report also said private emails from some of those targeted were made public through online posts including one in which correspondence between a Financial Times journalist and a researcher for a corporate intelligence firm was published in 2016. The Citizen Lab report said previous hacking cases indicated that such hacking was arranged “through a murky set of contractual, payment, and information-sharing layers that may include law firms and private investigators, and which allow clients a degree of deniability and distance”.

The Citizen Lab investigation was launched after it was contacted in 2017 by a Reuters journalist who had investigated Wirecard and was targeted by a phishing campaign, according to people familiar with the situation. A number of FT journalists were also targeted with emails purporting to be from friends and colleagues, in some cases using photographs lifted from social media accounts.

Matthew Earl (Photo: Dan Wilton)

On of the people targeted was financial researcher Matthew Earl, who at the time made money as a short seller. The NPR podcast episode clearly explains what happened to him and he’s also explicitely named in a Wall Street Journal story on Wirecard’s history with short sellers.

Wirecard made an aggressive defense against the criticism. Some investors said they purposely kept their short bets below the threshold required for disclosure for years to avoid catching the company’s attention.

Matthew Earl, who runs a research and investment firm called ShadowFall Capital & Research in London, spent more than £100,000 ($123,000) on legal and other fees defending himself when the company pursued him over critical reports in 2016. Under the name of Zatarra Research & Investigations, Mr. Earl and a former partner, Fraser Perring, accused Wirecard of corruption, corporate fraud and lax money-laundering controls in part related to illegal online gambling, allegations the company denied at the time. In December of 2016, Mr. Earl received letters from Wirecard’s outside lawyers that accused him of defamation and malicious falsehood among other things. He noticed a car parked outside his home, which followed him to the train station on at least one occasion. In one of the letters, reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, Wirecard’s lawyers, Jones Day, confirmed that “private investigators undertook limited and lawful surveillance.” They argued this was necessary to ensure he was available to receive an urgent letter and denied that it was “disruptive, persistent or intimidatory.” Jones Day declined to comment.

Mr. Earl, who has had no bets on the company’s shares since the Zatarra episode, and others, including Blue Ridge Capital, suffered cyberattacks, which they believed were connected to their Wirecard positions. The Citizen Lab, part of the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy at the University of Toronto, found in a report this month that hackers engaged in sustained targeting of short sellers, journalists and investigators working on topics related to Wirecard. Mr. Earl was one of those targeted by a group based in India, according to the report.

And as we know, Wirecard was actually to some extend being protected by BaFin.

Complicating matters for the shorts, Wirecard found allies in Germany’s financial regulator, BaFin. The government watchdog opened multiple investigations into potential market manipulation by Wirecard short sellers over the past decade, including against Mr. Earl. In 2019, after the Financial Times published a series of critical articles about Wirecard’s accounting, the company sued the newspaper. BaFin then opened a probe against the lead writer.

Yes, we now live in a world were private companies use shadowy attacks to intimidate and silence critics and people they don’t like. And not just any companies. Until a few weeks ago, Wirecard was a highly respected member of the German financial community. A member of the DAX, no less.

We have to assume that anyone can become a victim of extreme privacy invasions like this, not only short sellers, whistleblowers and journalists. Telling the truth and wanting to correct injustices in the wider society can suddenly become very perilous. And institutions of the state might not want to protect us either.

Feedback

Jonathan M.H. tells me:

Denmark just launched their corona app, closed source and allegedly private. If you want to flag yourself as positive, you need to login with the government approved 2 factor tool that everybody here has, where the user name is your unique citizen ID. <facepalm emoji>

If you have thoughts on the topics discussed in this episode, please feel free to contact me.

Toss a Coin to Your Podcaster

I am a freelance journalist and writer, volunteering my free time because I love digging into stories and because I love podcasting. If you want to help keep The Private Citizen on the air, consider becoming one of my Patreon supporters.

You can also support the show by sending money to  via PayPal, if you prefer.

via PayPal, if you prefer.

This is entirely optional. This show operates under the value-for-value model, meaning I want you to give back only what you feel this show is worth to you. If that comes down to nothing, that’s OK with me, pard. But if you help out, it’s more likely that I’ll be able to keep doing this indefinitely.

Thanks and Credits

I like to credit everyone who’s helped with any aspect of this production and thus became a part of the show.

Aside from the people who have provided feedback and research and are credited as such above, I’m thankful to Raúl Cabezalí, who composed and recorded the show’s theme, a song called Acoustic Routes. I am also thankful to Bytemark, who are providing the hosting for this episode’s audio file.

But above all, I’d like to thank the following people, who have supported this episode through Patreon or PayPal and thus keep this show on the air: Niall Donegan, Michael Mullan-Jensen, Jonathan M. Hethey, Georges Walther, Dave, Rasheed Alhimianee, Butterbeans, Kai Siers, Mark Holland, Steve Hoos, Shelby Cruver, Vlad, Fadi Mansour, Matt Jelliman, Joe Poser, Jackie Plage, 1i11g, ikn, Philip Klostermann, Dave Umrysh, Dirk Dede, David Potter, Vytautas Sadauskas, RikyM, drivezero, Mika, Jonathan Edwards, Barry Williams, Martin, Silviu Vulcan, S.J. and John Chandler.