How social smartphone apps like Strava, Polar and even Untappd can leak sensitive information about highly secret subjects by logging the runs and rides we take and even the beers we drink.

Welcome to The Private Citizen! Today we once again look at mobile apps and how they can be used to spy on people. I’m not trying to demonise apps or tell people not to use them, but rather sensitise you to things that could go wrong. If we are all aware and use apps responsibly, we can still reap their benefits without compromising too much of our privacy along the way. I believe it’s worth a try.

The Original Strava Story

At the start of 2018, The New York Times published a story on how the Fitness app Strava revealed sensitive military sites around the world. It turns out, soldiers like to go for a run and they like to be social about it, like the next man.

A fitness app that posts a map of its users' activity has unwittingly revealed the locations and habits of military bases and personnel, including those of American forces in Iraq and Syria, security analysts say. Since November, the company has published a global “heat map” showing the movements of people who have made their posts public. In the last few days, after the app’s oversharing was identified on Twitter by a 20-year-old Australian university student, security analysts have started to take note of that data, and some have argued that the map represents a security breach.

Strava “is sitting on a ton of data that most intelligence entities would literally kill to acquire,” Jeffrey Lewis of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, Calif., warned on Twitter. Some analysts have taken to social media to warn that, although the map does not name the people who traced its squiggles and lines, individual users can easily be tracked, by cross-referencing their Strava data with other social media use. That could put individual members of the military at risk, even when they are not in war zones.

The outlines of known military bases around the world are clearly visible on the map, especially in countries like Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, where few locals own exercise tracking devices. In those places, the heat signatures on American bases are set against vast dark spaces. Tobias Schneider, a security analyst, wrote on Twitter that “known Coalition (i.e. US) bases light up the night.” In Afghanistan, for instance, two of the largest coalition bases in the country – Bagram Airfield, north of Kabul; and Kandahar Airfield, in southern Afghanistan – can easily be picked out. The same is true for smaller bases around the country whose existence has long been public. But there also appear to be other airstrips and base-like shapes in places where neither the American-led military forces nor the Central Intelligence Agency are known to have personnel stations.

Perhaps more problematic for the military are the thin lines that appear to connect bases. Those lines seem likely to trace the roads or other routes most commonly used by American forces when traveling between locations, and their exposure could leave troops open to attack when they are most vulnerable.

The Pentagon did not directly address whether the heat map had revealed any sensitive location data. But Maj. Audricia Harris, a Pentagon spokeswoman, said that the Defense Department recommends that all its personnel limit their public social media profiles and that it was reviewing the situation. “Recent data releases emphasize the need for situational awareness when members of the military share personal information,” Major Harris said. The Pentagon “takes matters like these very seriously and is reviewing the situation to determine if any additional training or guidance is required,” the major added. The Central Intelligence Agency declined to comment.

The threat also extends to countries where the app is more popular. Dr. Lewis of the Middlebury Institute wrote in The Daily Beast that the pattern of movements clearly showed the location of Taiwan’s supposedly secret missile command center.

Strava is not the first program to collect far more information, including location data, than users realize, nor is it the first to make some of that information available to prying eyes, intentionally or not. Researchers at Kyoto University revealed in 2016 that they could find the precise locations of people who used popular dating sites, even when the users took steps to disguise that information. Last year, data was found online that would allow anyone to track more than half a million cars with GPS devices.

The company released a statement on Sunday noting that the app has privacy settings that can exclude users from the map and hide their activities from the general public. It urged people to read a blog post from last year about how to use those settings. The map “excludes activities that have been marked as private and user-defined privacy zones,” the company said. “We are committed to helping people better understand our settings to give them control over what they share.”

The Polar Investigation

Naturally, the problem wasn’t confined to Strava, as a Bellingcat investigation uncovered in July of the same year.

Polar, a fitness app, is revealing the homes and lives of people exercising in secretive locations, such as intelligence agencies, military bases and airfields, nuclear weapons storage sites, and embassies around the world, a joint investigation of Bellingcat and Dutch journalism platform De Correspondent reveals. In January Nathan Ruser discovered that the fitness app Strava revealed sensitive locations throughout the world as it tracked and published the exercises of individuals, including soldiers at secret (or, “secret”) military outposts. The discovery of those military sites made headlines globally, but Polar, which can feed into the Strava app, is revealing even more.

The manufacturing company known for making the world’s first wireless heart-rate monitor uses its site “Polar Flow” as a social platform where users can share their runs. Compared to the similar services of Garmin and Strava, Polar publicizes more data per user in a more accessible way, with potentially disastrous results. By showing all the sessions of an individual combined onto a single map, Polar is not only revealing the heart rates, routes, dates, time, duration, and pace of exercises carried out by individuals at military sites, but also revealing the same information from what are likely their homes as well. Tracing all of this information is very simple through the site: find a military base, select an exercise published there to identify the attached profile, and see where else this person has exercised. As people tend to turn their fitness trackers on/off when leaving or entering their homes, they unwittingly mark their houses on the map. Users often use their full names in their profiles, accompanied by a profile picture — even if they did not connect their Facebook profile to their Polar account.

Polar is not the only app doing this, but the difference between it and other popular fitness platforms, such as Strava or Garmin, is that these other sites require you to navigate to a specific person to view separate instances of his or her sessions, each exercise having its own small map. Moreover, they often limit the number of exercises that can be viewed. Polar makes it far worse by showing all the exercises of an individual done since 2014, all over the world on a single map. As a result, you only need to navigate to an interesting site, select one of the profiles exercising there, and you can get a full history of that individual.

With only a few clicks, a high-ranking officer of an airbase known to host nuclear weapons can be found jogging across the compound in the morning. From a house not too far from that base, he started and finished many more runs on early Sunday mornings. His favorite path is through a forest, but sometimes he starts and ends at a car park further away. The profile shows his full name. Activities normally shrouded in secrecy are laid bare with incredible detail. At a U.S. Air Force base where armed drones are stationed, an intelligence officer can be found exercising. Again, his name and profile picture openly available.

A selection of individuals that we found on the Polar site who were identifiable from their public information, and whose homes we where able to locate includes:

- Military personnel exercising at bases known, or strongly suspected, to host nuclear weapons. Individuals exercising at intelligence agencies, as well as embassies, their homes, and other locations.

- Persons working at the FBI and NSA.

- Military personnel specialised in Cyber Security, IT, Missile Defence, Intelligence and other sensitive domains.

- Persons serving on submarines, exercising at a submarine bases.

- Individuals both from management and security working at nuclear power plants.

- A CEO of a manufacturing company, exercising in locations all over the world.

- Americans in the Green Zone in Baghdad.

- Russian soldiers in Crimea.

- Military personnel at Guantanamo Bay.

- Troops stationed near the North Korean border.

- Airmen involved in the battle against the Islamic State.

This list is not exhaustive. We were able to scrape Polar’s site (another security flaw) for individuals exercising at 200+ of such sensitive sites, and we gathered a list of nearly 6,500 unique users. Together, these users had made over 650.000 exercises, marking the places they work, live, and go on vacation.

The security implications are obviously grave. In countries where soldiers were banned from wearing their uniforms on the street in the off-chance that they would run into a potential terrorist, addresses and living patterns can now be found easily by anyone with internet access and the wits to use Polar’s site. In its current form, it is not difficult to find the time of deployment, home, photograph, and the function of a soldier in a conflict zone. It does not take much imagination to see how this information could be used in dangerous ways by extremists or state intelligence services. This is especially concerning considering the data we managed to gather on personnel at multiple nuclear weapons storage sites. The risk from Polar’s open data set also poses a risk to civilians, as those with ill intentions could use Polar to see when, and for how long, users in an area tend to be away from their homes, as well as when they are abroad if they bring the heart rate sensors with them.

On registering your account, Polar asks you to provide a name, location, height, weight, date of birth, gender and the amount of training per week. Though you can obviously fill in fake information, the majority of users we surveyed provided what seems to be reliable information. Along with the ability to connect your account to Facebook, Polar also offers integration with five other apps (including Strava) to share “all your sessions automatically”.

As a result of these stories, the Pentagon proceeded to ban all private use of GPS devices by military personnel later in 2018.

The new rules prohibit defense personnel to use fitness trackers, any applications in mobile devices which use GPS, as well as any “other devices and apps that pinpoint and track the location of individuals”. Reiterating the fact, Pentagon spokesman Army Col. Robert Manning III said, “Effective immediately, Defense Department personnel are prohibited from using geolocation features and functionality on government and nongovernment-issued devices, applications and services while in locations designated as operational areas.”

And now… Tracking People via Untappd

Well, it turns out you don’t really need a GPS app to track military and intelligence personnel. You just need an app. In another story, published last month, Bellingcat analysed data from the social drinking app Untappd to accomplish this.

The beer-rating app Untappd can be used to track the location history of military personnel. The social network has over eight million mostly European and North American users, and its features allow researchers to uncover sensitive information about said users at military and intelligence locations around the world.

For people in the military, neither drinking beer nor using social media is newsworthy on its own. But Untappd users log hundreds, often thousands of time-stamped location data points. These locations are neatly sorted in over 900 categories, which can be as diverse and specific as “botanic garden”, “strip club”, “gay bar”, “west-Ukrainian restaurant”, and “airport gate”. As the result of this, the app allows anyone to trace the movements of other users between sensitive locations – as well as their favorite bars, hotels, restaurants, neighbourhoods, and, sometimes, even private residences.

Examples of users that can be tracked this way include a U.S. drone pilot, along with a list of both domestic and overseas military bases he has visited, a naval officer, who checked in at the beach next to Guantanamo Bay’s detention center as well as several times at the Pentagon, and a senior intelligence officer with over seven thousand check-ins, domestic and abroad. Senior officials at the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Air Force are included as well.\

Cross-referencing these check-ins with other social media makes it easy to find these individuals’ homes. Their profiles and the pictures they post also reveal family, friends, and colleagues. The activity level varies per location. Some locations currently have a lot of active users while other locations were briefly used years ago, such as Blackwater / XE’s location in North Carolina. Even the inactive locations can still reveal a lot of data about the visitors and their networks.

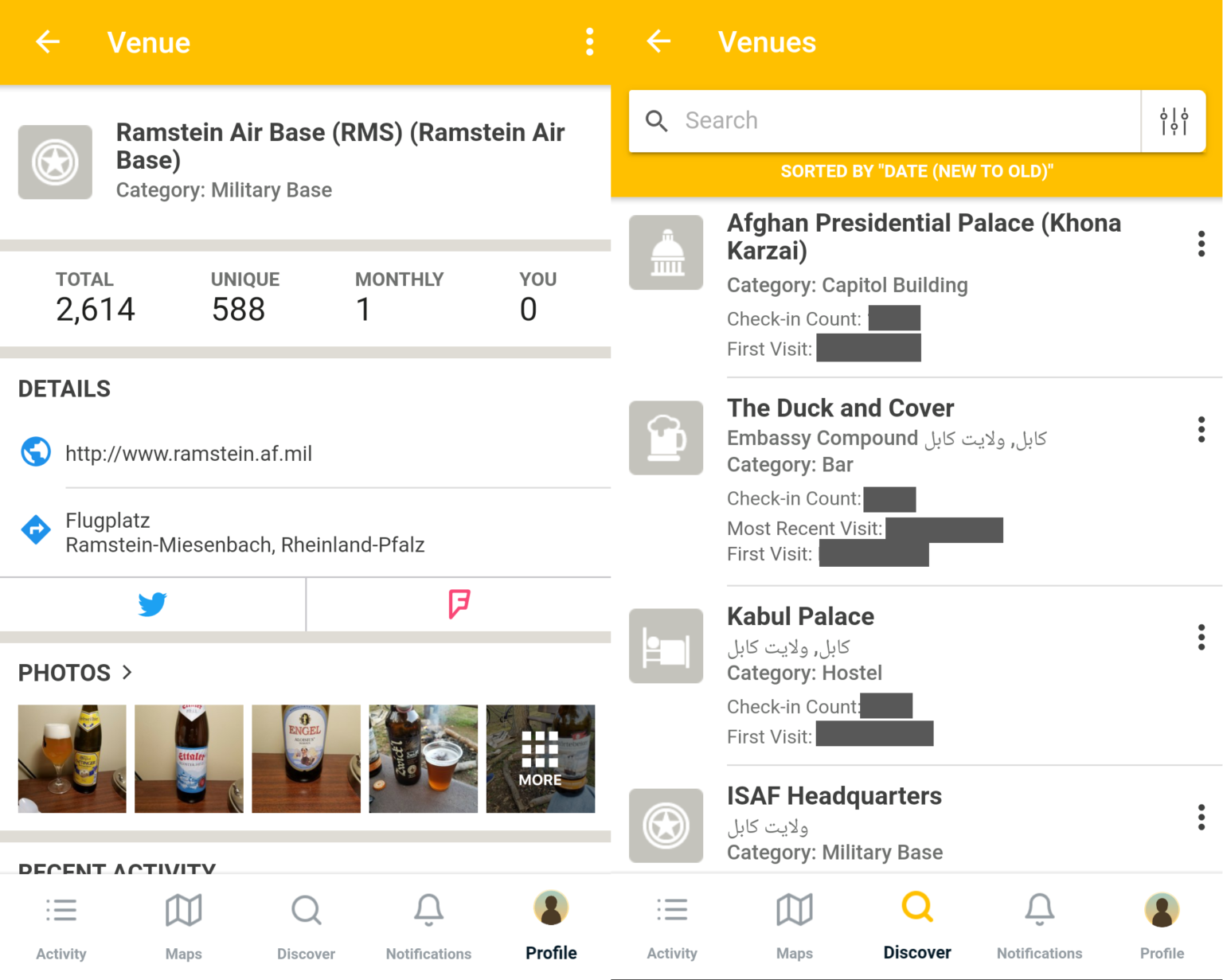

Below are examples of a location page and a user’s venue history. On the left is the venue page for Ramstein air base, showing nearly 600 unique visitors that have logged over 2600 beers. On the right, we see a small portion of a single user’s check-in history as he travelled through Afghanistan, revealing his visits to the United States embassy bar in Kabul, the Duck and Cover, among other places. The user also has thousands of other check-ins spread over hundreds of different locations.

A military user’s check-in history in Untappd (Source: Bellingcat)

A military user’s check-in history in Untappd (Source: Bellingcat)

At first glance Untappd’s data might seem useless as its location data is not strict, meaning users are free to check in to locations from up to 60 miles away. This is a problem at well-known spots in more populated areas. For example, the NSA and MI6 headquarters have many check-ins from users who were in the vicinity, but who were likely not inside these buildings. Moreover, it can be difficult to find locations of interest, as Untappd’s search functions only list venues such as hotels, bars, and restaurants. You cannot search for locations that are tagged primarily as “government building” or “military base”, for example.

So how do we actually go about finding these locations and the people who checked in there?

When users drink beer, they can “check in” to Untappd by taking a picture of their beverage and logging their location as well as the date and time. Searching for a location brings up only bars, restaurants and shops. Once you begin the process of “checking in” a beer, however, Untappd allows more locations to be selected. Locations have their own profiles, showing all users who have checked in there, along with the date and time of their check-in. These locations are drawn from Foursquare’s application programming interface (API), and are highly categorized. Searching for military locations does not bring up results. Yet by finding members of the military and piggybacking, you can find other military locations.

Let’s take Camp Peary, a U.S. military reservation officially referred to as an Armed Forces Experimental Training Activity, though more commonly known as “The Farm.” The location hosts training facilities for personnel from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and has an airstrip which allegedly has been used for rendition flights. Beginning with a simple search in both Untappd and Google, we can easily find the landing strip at Camp Peary. However, Camp Peary itself does not show up. However, if we search for “Camp Peary” directly in the Foursquare listings, Foursquare now gives a result for Camp Peary (though the location does not include useful information). Untappd appears to actively hide some location categories, including “military base”, from its search results.

Yet there is one more way Untappd can be searched: by checking in the actual beer. When users log their drink, Untappd can use their device location to suggest other places nearby to check-in. If we spoof our location to Camp Peary’s vicinity and begin the process of checking in a beer, Untappd will reveal that it does know Camp Peary exists. Completing the “check-in” will log the beer on your timeline, along with a link to Camp Peary’s page. On Camp Peary’s page, we can find a timeline of users who have checked-in there, as well as photos associated with the location.

The best way to determine whether a user was really in the location to which they checked in is to look at the pictures taken there. Untappd encourages users to upload photos of their beer bottles in order to identify their drinks, and these pictures sometimes include background clues. These background clues allow for geolocation of these images to verify the location of the users who uploaded the pictures.

Continuing to use Camp Peary as our example, we can see pictures have been posted by an individual who has checked in three times. Through geolocation, we can match the features in the picture to satellite imagery of buildings within Camp Peary’s compound. We can also use Untappd’s profile data to confirm the person’s identity by cross-referencing the username and profile picture with other social media.

Matching a picture of a beer bottle with a location within Camp Peary (Source: Bellingcat)

Matching a picture of a beer bottle with a location within Camp Peary (Source: Bellingcat)

Another way to verify the authenticity of check-ins is to browse a user’s profile. A user profile has a timeline, but also a venue list and a list of photos uploaded with each check in. The timeline is limited to the last 365 entries, but the photo list and venue list are unlimited, meaning it is possible to get a full location history. This allows us to get a higher degree of certainty about a user’s check-ins before beginning to verify the user’s photos and cross-referencing with other social media. For example, a user that has visited several military locations across large distances, multiple times, over a longer period of time, is more likely to be associated with that location than a user who has only checked in there once.

For example, the user who checked in at Camp Peary has also checked in at military locations throughout the Middle East, and has logged an additional 700+ check-ins at 500+ unique locations. A similar check of the user near the Guantanamo Bay detention center shows that he paid several visits to the Pentagon, as well as other military installations. Again, through their check-in history and cross-referencing with other open sources, we can identify the user in question.

Through the location history of a user identified at a military location, it becomes possible to discover other military locations. Each new military location might reveal other users, and those users might in turn reveal new military locations. In other words, we can now piggyback on users we have identified by looking at their location histories, instead of having to spoof our location and check in. If you visit Untappd venue locations through the web rather than the app, they will list “loyal patrons,” the top 15 users that have checked in most frequently at that location. These are perfect candidates to piggyback on, as they are both likely to have a strong connection to that location, and be active users that will be checking in elsewhere as well. By comparing the location history of several different users, it also becomes possible to identify non-military locations that they have in common. Think, for example, about bars and restaurants near sensitive locations that their visitors might go to in their spare time. In the Dutch example, it is possible to identify a resort soldiers went to after a mission, in order to transition from military to civilian life.

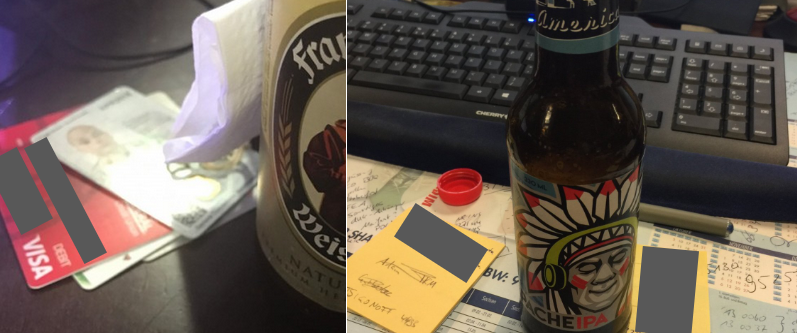

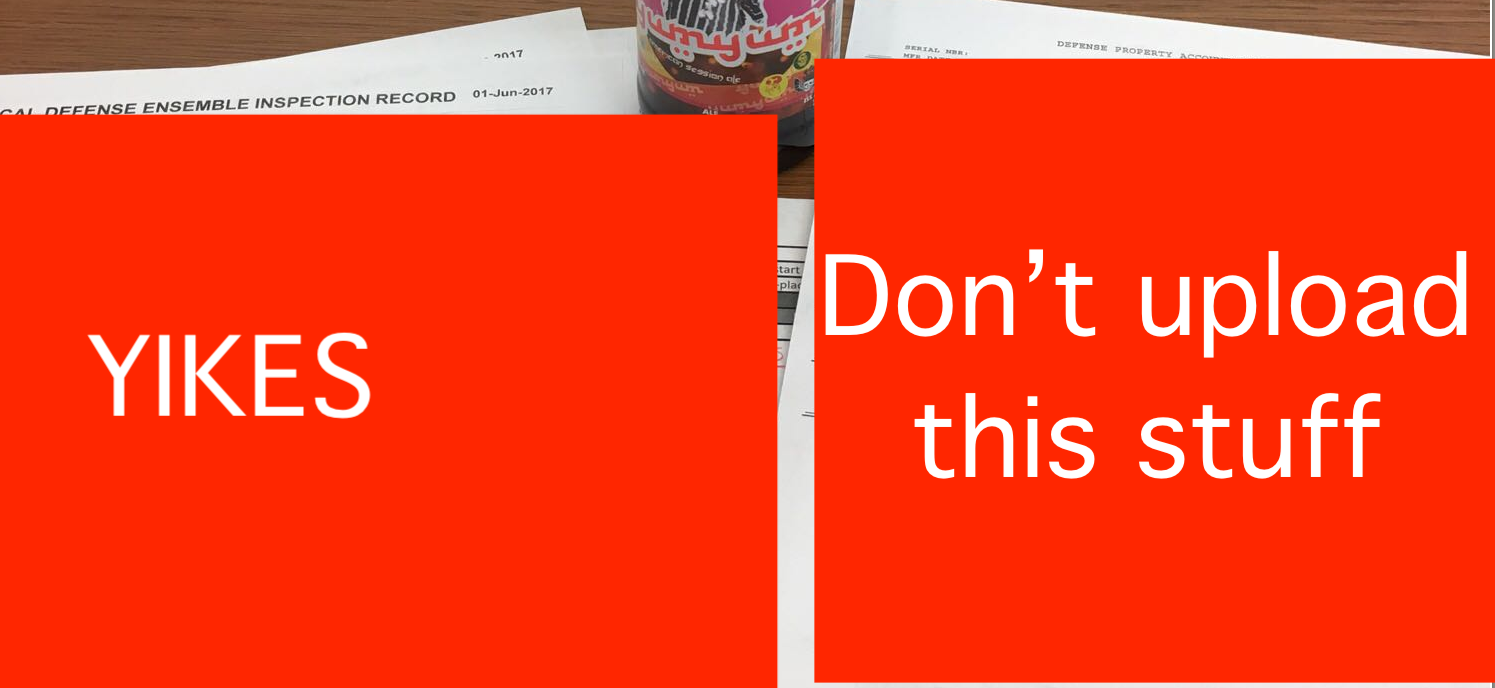

As with any social media, the photos can reveal more information on their own too. The difference is that with Untappd, the photos tend to focus a bit more on tables or desks where users place the bottle, and that they might be taken by slightly inebriated users a bit more often. They include desktops, documents and plane tickets, but they also feature military hardware from time to time. Below are pictures taken at military installations.

Beer bottles surrounded by sensitive stuff (Source: Bellingcat)

Beer bottles surrounded by sensitive stuff (Source: Bellingcat)

In our previous investigation of a fitness app revealing the homes of military and intelligence personnel, we did not publish the findings until the company behind the app rendered the data inaccessible and made changes to its privacy standards. This is not the case with Untappd.

Untappd differs in three crucial ways: It has decent privacy settings, as profiles can be set to “private” easily. Users have to consciously select locations they check in to. Most importantly, private residences are not registered unless a user has added their own home. In other words, with Untappd, the onus is on the user for the data they share.

At the same time, Untappd’s data can be a useful source of potential leads for investigations, or as a point of reference to confirm other findings. This article has focused on the military, but businesses and political locations can be found there as well. It is a stark reminder that Untappd and smaller social networks like it, though they tend to draw less attention, are worth checking when conducting open source investigations – and can also present serious security challenges.

Feedback

Our anonymous Canadian listener chimes in again, concerning episode 22:

I also do not believe that the current situation in the US is fully about race but more about division of people. I have included this article from last year where there was a similar murder there, except the victim was an upper middle class white male, and none of the 3 officers involved ended up going to court. As we can see, there was very limited coverage of this incident, despite the similarities.

Here in Canada, our Prime Minister has just announced that we are a racist nation and more must be done to address our racism against the native people of our country. And I am sure you have heard about the blockades we suffered through the end of last year where native backed protesters shut down our highways and railways. I would think that from the outside, we must look like a racist and oppressive nation when considering these issues.

What the media fails to report on, and our Prime Minister will never mention, is that this is also a government backed issue. For instance, no one ever mentions that the native people here can be and are frequently granted housing, paid for by their bands, through financing received from our government. Or that while I pay 33% of my wages to taxes before I get my money from my employer, and a further 13% in taxes whenever I spend my money, they are exempt from the 33% tax if they live in the aforementioned housing, and also exempt in many locations from the further 13% tax. While I had to take out loans to pay for my post secondary schooling, they receive grants through their bands and our government for this same schooling. While our government now bans close to 2,000 firearms from citizens of the country (the list has been growing weekly), they created an exemption to allow the native people to continue owning and using these firearms. While citizens of this country must obtain schooling, licensing, and obtain a permit to hunt or fish, and then only in set areas and seasons, the native people are allowed to hunt or fish to their hearts desire.

To me, this is less about “racism”, and more about government engineered division of the people. How can people truly be equal if we are declared unequal by our own governments?

Thanks for your continued reporting and keep up the great work.

Fadi Mansour comments on the same episode:

First of all, I think I understand where you are coming from, and I believe I share your thoughts, but I think it’s a very tricky subject. And I thank you for the effort to try to approach it.

I totally agree, that differences should not be things to separate us, but to enrich us. But sadly, any slogan (Black Lives Matter, All Lives Matter), could be used with good intentions, and bad intentions, and this is the core issue: People with bad intentions. It’s sad to see people being killed, but at the same time, it’s sad to see the division between people, and instead of helping each other, resentment is being fuelled: By people looting, and by law enforcement heavy-handedly reacting. It’s really difficult for people in these situations to be rational and considerate at these moments, but this is what is needed.

On another note: I support your suggestion to encourage people who like to beat each other out, to get into cage fights. Maybe they can get it out of their system! And I liked your way of explaining religion, it’s hard now to get it out of my mind.

Martin says:

On a recent show you expressed surprise at the BBC spreading misinformation, and wondered what their agenda might be.

He sent me some ideas regarding this, especially with regards to the Scottish independence movement. I think this is the point where I explain what a rhetorical question is.

If you also have thoughts on the topics discussed in this episode, please feel free to contact me.

Toss a Coin to Your Podcaster

I am a freelance journalist and writer, volunteering my free time because I love digging into stories and because I love podcasting. If you want to help keep The Private Citizen on the air, consider becoming one of my Patreon supporters.

You can also support the show by sending money to  via PayPal, if you prefer.

via PayPal, if you prefer.

This is entirely optional. This show operates under the value-for-value model, meaning I want you to give back only what you feel this show is worth to you. If that comes down to nothing, that’s OK with me, pard. But if you help out, it’s more likely that I’ll be able to keep doing this indefinitely.

Thanks and Credits

I like to credit everyone who’s helped with any aspect of this production and thus became a part of the show.

Aside from the people who have provided feedback and research and are credited as such above, I’m thankful to Raúl Cabezalí, who composed and recorded the show’s theme, a song called Acoustic Routes. I am also thankful to Bytemark, who are providing the hosting for this episode’s audio file.

But above all, I’d like to thank the following people, who have supported this episode through Patreon or PayPal and thus keep this show on the air: Niall Donegan, Michael Mullan-Jensen, Jonathan M. Hethey, Georges Walther, Dave, Rasheed Alhimianee, Butterbeans, Kai Siers, Mark Holland, Steve Hoos, Shelby Cruver, Vlad, Fadi Mansour, Matt Jelliman, Joe Poser, Jackie Plage, 1i11g, ikn, Philip Klostermann, Dave Umrysh, Dirk Dede, David Potter, Vytautas Sadauskas, RikyM, drivezero, Mika, Jonathan Edwards, Barry Williams, Martin, Silviu Vulcan and S.J.