A look at the Ring video doorbell, which started as a great idea to protect your home from burglars and which turned, with a little bit of help from Silicon Valley investors and your local police department, into one of the biggest surveillance nightmares of modern day urban life.

How do you do? On today’s episode of The Private Citizen, I want to talk about Amazon’s subsidiary Ring. How the company was founded, what the problems with their software security are and how they are colluding with local police departments to build a private sector surveillance architecture in the US and parts of Europe.

But before we start, I have some housekeeping to take care of: I had some issues with the RSS feed of the podcast. If you are missing episodes or see other irregularities, please force a feed refresh in your podcatcher. If that doesn’t help, try unsubscribing, deleting all cached data and resubscribing. I apologise for the inconvenience! Sometimes, podcasting is hard…

The Origins of Ring Inc.

Wikipedia: Ring Inc.

Ring was founded in 2013 as Doorbot by Jamie Siminoff. Doorbot was crowdfunded via Christie Street, and raised US$364,000; more than the $250,000 requested. In 2013, Siminoff and Doorbot appeared on an episode of the reality series Shark Tank to seek a $700,000 investment in the company, which he estimated was worth $7 million. Kevin O’Leary made an offer as a potential investor that Siminoff declined. After being on Shark Tank, Siminoff rebranded the company and it received $5 million in additional sales. In 2016, Shaquille O’Neal acquired an equity stake in Ring, and subsequently became a spokesperson in the company’s marketing. Since then, the company raised more than $200 million in investments and counts Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers, Qualcomm Ventures, Goldman Sachs, DFJ Growth and Sir Richard Branson as prominent investors. Ring was acquired by Amazon in February 2018 for an estimated value of between $1.2 billion and $1.8 billion.

Business Insider: This guy turned his failure on “Shark Tank” into a $109 million investment from Goldman Sachs

His company made a video doorbell that connected to your smartphone so you could remotely see and talk to the person at the door through your mobile device. The idea was largely based on the idea that a burglar tends to ring the bell before breaking in. With DoorBot, you could see who is at the door and even pretend you’re at home when you’re not, making it a convenient home-security device.

Siminoff was already making about $1 million in sales annually then, and he had high hopes of getting one of the TV show’s “sharks” in as investors of his company. But the sharks weren’t impressed. One by one, the sharks dropped out, leaving only Kevin O’Leary, also known as “Mr. Wonderful,” as the last potential investor. O’Leary’s offer wasn’t too enticing. He would offer a $700,000 loan, then take 10% of all sales until the loan was paid off. After that, O’Leary wanted to collect a 7% royalty on all future sales, plus 5% of the company’s equity. Siminoff rejected the offer and walked away with nothing. It was a public moment of humiliation, but one that didn’t deter the fast-growing Los Angeles company – although it did help Ring rebrand to convey a more serious image.

“Jamie, to his credit, is an experienced entrepreneur. He’s playing to win,” CRV investor Saar Gur told Business Insider. “He has a very ambitious vision for where the company goes over time.” The company has expanded from doorbells with cameras to a whole line of outside-the-house security. Its latest product is a security camera that has floodlights and a siren in addition to the two-way talk, so you can yell at a burglar and turn on a siren if you see an intruder approaching. “The idea that I have a siren on my smartphone to scare people away – that’s a new product,” Gur said. “He’s seeing the world is different and inventing products from scratch.”

Little Respect for People’s Privacy

The Intercept: For owners of Amazon’s Ring security cameras, strangers may have been watching too

Ring has a history of lax, sloppy oversight when it comes to deciding who has access to some of the most precious, intimate data belonging to any person: a live, high-definition feed from around – and perhaps inside – their house. The company has marketed its line of miniature cameras, designed to be mounted as doorbells, in garages, and on bookshelves, not only as a means of keeping tabs on your home while you’re away, but of creating a sort of privatized neighborhood watch, a constellation of overlapping camera feeds that will help police detect and apprehend burglars (and worse) as they approach. “Our mission to reduce crime in neighborhoods has been at the core of everything we do at Ring,” founder and CEO Jamie Siminoff wrote last spring to commemorate the company’s reported $1 billion acquisition payday from Amazon, a company with its own recent history of troubling facial recognition practices. The marketing is working; Ring is a consumer hit and a press darling.

cf. The Washington Post: Amazon is selling facial recognition to law enforcement – for a fistful of dollars

Beginning in 2016, according to one source, Ring provided its Ukraine-based research and development team virtually unfettered access to a folder on Amazon’s S3 cloud storage service that contained every video created by every Ring camera around the world. This would amount to an enormous list of highly sensitive files that could be easily browsed and viewed.

At the time the Ukrainian access was provided, the video files were left unencrypted, the source said, because of Ring leadership’s “sense that encryption would make the company less valuable,” owing to the expense of implementing encryption and lost revenue opportunities due to restricted access. The Ukraine team was also provided with a corresponding database that linked each specific video file to corresponding specific Ring customers.

At the same time, the source said, Ring unnecessarily provided executives and engineers in the U.S. with highly privileged access to the company’s technical support video portal, allowing unfiltered, round-the-clock live feeds from some customer cameras, regardless of whether they needed access to this extremely sensitive data to do their jobs. For someone who’d been given this top-level access only a Ring customer’s email address was required to watch cameras from that person’s home.

The source also recounted instances of Ring engineers “teasing each other about who they brought home” after romantic dates.

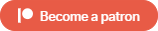

Screenshots of an internal application from Ring’s Ukrainian R&D lab (redaction by The Intercept) (Source: The Intercept)

Screenshots of an internal application from Ring’s Ukrainian R&D lab (redaction by The Intercept) (Source: The Intercept)

A never-before-published image from an internal Ring document pulls back the veil of the company’s lofty security ambitions: Behind all the computer sophistication was a team of people drawing boxes around strangers, day in and day out, as they struggled to grant some semblance of human judgment to an algorithm.

This process is still apparently underway years later: Ring Labs, the name of the Ukrainian operation, is still employing people as data operators, according to LinkedIn, and posting job listings for vacant video-tagging gigs.

BuzzFeed News: Ring Is Using Its Customers' Doorbell Camera Video For Ads. It Says It’s Allowed To.

Amazon’s doorbell camera company Ring is featuring its customers' home security footage in Facebook advertisements, encouraging people to identify and report suspected criminals to the police. The company is able to do this thanks to a broad terms of service agreement that grants it the perpetual right to use footage shared with it for “any purpose” it chooses.

According to Ring’s own terms of service, the company has the right to use video shared by customers, particularly via Neighbors, the crime-watching social platform Ring launched in 2018 to compete with the likes of the popular Citizen app. But unlike Citizen, Ring has struck formal deals with multiple law enforcement agencies across the US. Ring says it asks its users for “explicit consent” so law enforcement can use customers' footage. Buried in Ring’s terms of service agreement, under the “Shared Content” section – the section that explains the specific rules for content that users share to Neighbors – the company says when law enforcement sends a request to a user, asking them to share information and the user agrees, or if a user chooses to share that content themselves, Ring’s terms of service “grants Ring an expansive copyright license in any shared content, which includes content shared via the Neighbors function.”

Ring and the Police

CNet: Amazon’s helping police build a surveillance network with Ring doorbells

While residential neighborhoods aren’t usually lined with security cameras, the smart doorbell’s popularity has essentially created private surveillance networks powered by Amazon and promoted by police departments. Police departments across the country, from major cities like Houston to towns with fewer than 30,000 people, have offered free or discounted Ring doorbells to citizens, sometimes using taxpayer funds to pay for Amazon’s products. While Ring owners are supposed to have a choice on providing police footage, in some giveaways, police require recipients to turn over footage when requested.

WOWT / NBC Omaha (video): Relationship between police and Ring doorbell cameras

“The information that we’re able to view is all public information.”

Tweakers: Gouda geeft subsidie voor camera of videodeurbel bij aanmelden politiedatabase

- Gemeente Gouda: Subsidie voor inbraakwerende maatregelen

- Ring Subsidy Match Program

- Gizmodo: Ring Gave Police Stats About Users Who Said “No” to Law Enforcement Requests

Amazon’s home security company Ring tracked how its users responded to law enforcement requests for surveillance footage captured by Ring devices, and it provided overviews of that data to police departments upon request. In emails obtained by Gizmodo, Ring informed a Florida police department about the number of times residents had refused police access to their cameras or ignored their requests altogether.

According to Ring, when police seek to acquire footage from its customers – who must also be users of Neighbors, its “neighborhood watch” app – police are not informed of which residents receive the requests or how many cameras may have captured the footage they seek. The requests are sent out in emails stating that Ring is assisting a particular officer with an investigation. They are received automatically by device owners within a certain range of an address provided by police.

Fort Lauderdale entered into a partnership with Ring in March 2018 giving it access to this capability. One document obtained by Gizmodo claims the city had, as of that April, some 20,000 Ring owners, though it’s unclear how many had downloaded the Neighbors app at that time. According to a September 2018 email, Fort Lauderdale police had roughly a 3.5 percent success rate when requesting footage. Of the 319 total videos sought, they received permission to view only 11. The data was provided to the department after one officer asked to know how many times officers were successful in soliciting a response. “The Chief would like to know this ASAP,” he said. “[W]e are working on adding more data points but this will give the Chief an idea of how your video requests are doing so far,” a Ring employee replied.

CNet: Ring let police view map of video doorbell installations for over a year

For more than a year, police departments partnered with Amazon’s Ring unit had access to a map showing where its video doorbells were installed, down to the street, public documents revealed. So while Ring said it didn’t provide police with addresses for the devices, a feature in the map tool let them get extremely close. The feature was removed in July.

The heat maps feature was one of several surveillance tools that Ring told police “should not be shared with the public.” The first Ring police partnership listed started in March 2018, and the video doorbell company had at least 335 police partners by the time it disabled the feature, records show.

Gizmodo: Ring’s Hidden Data Let Us Map Amazon’s Sprawling Home Surveillance Network

Even as its creeping objective of ensuring an ever-expanding network of home security devices eventually becomes indispensable to daily police work, Ring promised its customers would always have a choice in “what information, if any, they share with law enforcement.” While it quietly toiled to minimize what police officials could reveal about Ring’s police partnerships to the public, it vigorously reinforced its obligation to the privacy of its customers – and to the users of its crime-alert app, Neighbors.

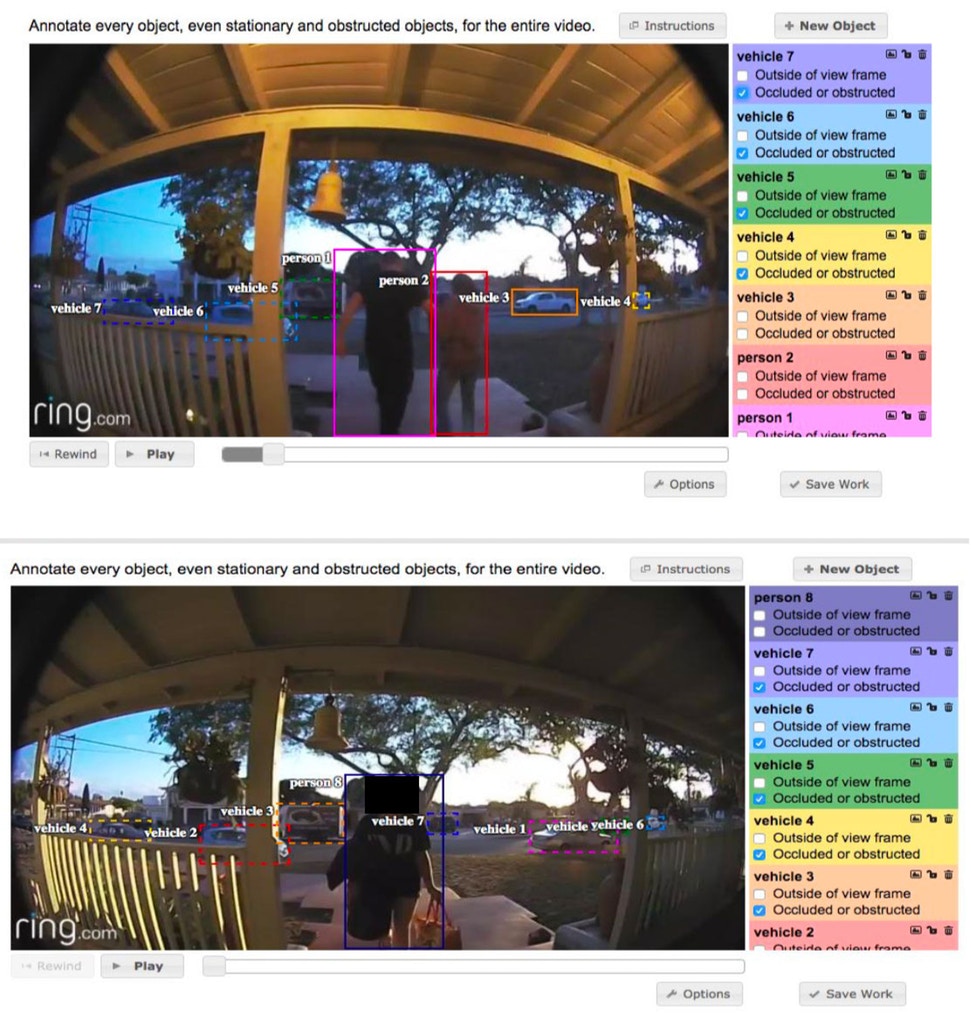

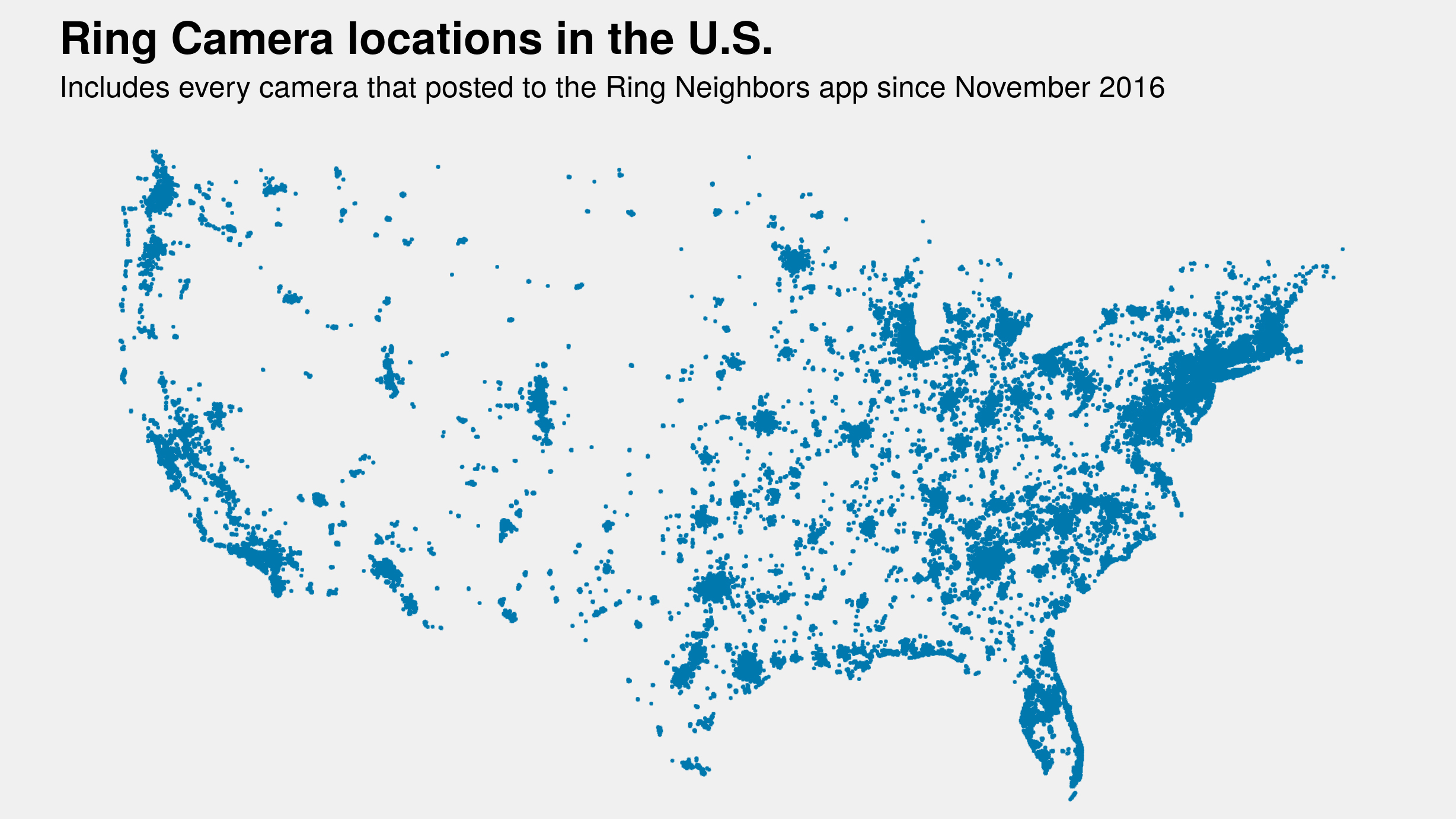

However, a Gizmodo investigation, which began last month and ultimately revealed the potential locations of up to tens of thousands of Ring cameras, has cast new doubt on the effectiveness of the company’s privacy safeguards. It further offers one of the most “striking” and “disturbing” glimpses yet, privacy experts said, of Amazon’s privately run, omni-surveillance shroud that’s enveloping U.S. cities.

Gizmodo could access the locations of 440,000 Ring cameras spread all over the continental US (Source: Gizmodo)

Gizmodo could access the locations of 440,000 Ring cameras spread all over the continental US (Source: Gizmodo)

Ring cameras in Los Angeles, California (Source: Gizmodo)

Ring cameras in Los Angeles, California (Source: Gizmodo)

Gizmodo has acquired data over the past month connected to nearly 65,800 individual posts shared by users of the Neighbors app. The posts, which reach back 500 days from the point of collection, offer extraordinary insight into the proliferation of Ring video surveillance across American neighborhoods and raise important questions about the privacy trade-offs of a consumer-driven network of surveillance cameras controlled by one of the world’s most powerful corporations. And not just for those whose faces have been recorded. Examining the network traffic of the Neighbors app produced unexpected data, including hidden geographic coordinates that are connected to each post –latitude and longitude with up to six decimal points of precision, accurate enough to pinpoint roughly a square inch of ground. Using the hidden coordinates, Gizmodo was able to produce detailed maps depicting the locations of tens of thousands of Ring cameras across 15 U.S. cities with varying degrees of accuracy.

Ring Has Shitty Security

Bitdefender: Ring Video Doorbell Pro Under the Scope

The device uses a wireless connection to join the local network. When first configuring the device, the smartphone app must send the wireless network credentials. This takes place in an unsecure manner, through an unprotected access point. When entering configuration mode, the device creates an access point without a password (the SSID contains the last three bytes from the MAC address). Once this network is up, the app connects to it automatically, queries the device, then sends the credentials to the local network. All these exchanges are performed through plain HTTP. This means the credentials are exposed to any nearby eavesdroppers. This can be exploited by a nearby attacker to obtain the user’s network credentials. The attacker must trick the user into believing that the device is malfunctioning so the user reconfigures it. One way to do this is to continuously send deauthentication messages, so that the device is dropped from the wireless network

Vice: We Tested Ring’s Security. It’s Awful

Ring is not offering basic security precautions, such as double-checking whether someone logging in from an unknown IP address is the legitimate user, or providing a way to see how many users are currently logged in – entirely common security measures across a wealth of online services. Ring doesn’t appear to check a user’s chosen password against known compromised user credentials. Although not a widespread practice, more online services are starting to include features that will alert a user if they’re using an already compromised password. Other steps Ring could take to better keep hackers out includes checking for concurrent sessions, such as seeing whether the user is simultaneously logged in from, say, both Germany and the U.K. One member of a hacking forum who codes cracking tools, and who Motherboard granted anonymity so they could speak more openly about the process, said, “just enabling SMS verification if there is a connection from an unknown IP would instantly kill each checker.” A checker is a piece of software that grinds through credentials to see if they work on a particular site or service.

Ring hackers' software works by rapidly checking if an email address and password on the Ring web login portal works; hackers will typically use a list of already compromised combinations from other services. If someone makes too many incorrect requests to login, many online services will stop them temporarily from doing so, mark their IP address as suspicious, or present a captcha to check that the user trying to login is a human rather than an automated program. Ring appears to have minimal protections in place for this though. Ring does offer two-factor authentication, where a user is required to enter a second code sent to them as well as their password, but Ring does not force customers to use it.

A Ring account is not a normal online account. Rather than a username and password protecting messages or snippets of personal information, such as with, say, a video game account, breaking into a Ring account can grant access to exceptionally intimate and private parts of someone’s life and potentially puts their physical security at risk. Some customers install these cameras in their bedrooms or those of their children. Someone with access can hear conversations and watch people, potentially without alerting the victims that they are being spied on. The app displays a user-selected address for the camera, and the live feed could be used to determine whether the person is home, which could be useful if someone were, for example, planning a robbery. Once a hacker has broken into the account, they can watch not only live streams of the camera, but can also silently watch archived video of people – and families – going about their days. Or a hacker can digitally reach into those homes, and speak directly to the bewildered, scared, or confused inhabitants.

cf.: Two-Factor Security Authentication with Ring Products

It Was Only a Matter of Time Until This Was Going to Be Abused

The New York Times: Somebody’s Watching: Hackers Breach Ring Home Security Cameras

Ashley LeMay and Dylan Blakeley recently installed a Ring security camera in the bedroom of their three daughters, giving the Mississippi parents an extra set of eyes – but not the ones that they had bargained for. Four days after mounting the camera to the wall, a built-in speaker started piping the song “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” into the empty bedroom, footage from the device showed. When the couple’s 8-year-old daughter, Alyssa, checked on the music and turned on the lights, a man started speaking to her, repeatedly calling her a racial slur and saying he was Santa Claus. She screamed for her mother. The family’s Ring security system had been hacked, the family said. The intrusion was part of a recent spate of breaches involving Ring, which is owned by Amazon.

Global News (video): Hacker hurls racial slurs at family after breaking into home Ring camera

Vice: Inside the Podcast that Hacks Ring Camera Owners Live on Air

The NulledCast is a podcast livestreamed to Discord. It’s a show in which hackers take over people’s Ring and Nest smarthome cameras and use their speakers to talk to and harass their unsuspecting owners.

“Sit back and relax to over 45 minutes of entertainment,” an advertisement for the podcast posted to a hacking forum called Nulled reads. “Join us as we go on completely random tangents such as; Ring & Nest Trolling, telling shelter owners we killed a kitten, Nulled drama, and more ridiculous topics. Be sure to join our Discord to watch the shows live.”

After the recent media attention about Ring hacks, Nulled members are scrambling to remove evidence of the Ring hacks and distance themselves from the practice. “Hey NulledCast fans, we need to calm down on the ring trolling, we have 3 investigations and two of us are already probably fucked,” one of the self-described podcast staff wrote on a NulledCast Discord server that Motherboard gained access to. “Drop suggestions on what else we should do. It will still happen just on a much smaller scale,” they added.

The Verge: Amazon’s Ring has been blaming reused passwords, but now thousands of logins have leaked

Amazon’s Ring is having a very bad week. BuzzFeed News first reported today that login credentials for thousands of Ring camera owners have been published online, including 3,672 sets of emails, passwords, time zones, and the names given to specific Ring cameras (“front door” or “kitchen,” for example). Later today, TechCrunch reported on a set of 1,562 credentials, also consisting of unique email addresses, passwords, time zones, and a camera’s named location. It’s unclear if there’s overlap in the two datasets, but TechCrunch said that its data “appears to be a similar-looking data set to that which [BuzzFeed News] obtained.”

- Vice: How Hackers Are Breaking Into Ring Cameras

- The Verge: Why Ring can’t just blame users for those home-invading camera “hacks”

- Heise: Der Hacker im Smart Home: Amazons Ring-Kameras werden immer öfter gehackt

- Heise: Angriffe häufen sich: Tausende Passwörter für Ring-Kameras im Netz verbreitet

After my own coverage (see the two Heise articles linked above), I received an email from Ring’s German PR contact with the following talking points (translated from German):

- Ring has no evidence of unauthorised access to their systems or of a danger to Ring’s network.

- Ring was recently made aware of isolated attacks on the accounts of some Ring users. Login credentials for these attacks were obtained from online services that are not under Ring’s control.

- As soon as those attacks became public, Ring has closed down unauthorised access to the effected accounts.

- Users have full control of the video material captured by their Ring cameras. The Neighbors app (which is only available in the US) only exposes footage publicly that users have posted themselves knowingly. Police departments access this information with the same UI as other users; neither do they have access to additional information nor the exact location or identity of the user posting the footage. The police only has access to publicly available footage, unless the user decides himself to give them additional materials.

- The programme in Gouda is an independent initiative that has no connection to Ring whatsoever.

- Ring does not share customer information with government agencies, unless it receives a valid and legally binding court order. As a matter of course, Ring denies all other requests for such information.

Feedback

I was talking to new producer Jackie Plage on Patreon and she said something that really cracked me up:

I haven’t even gotten around to listening to any episodes of your latest podcast yet, I’m the worst fan you ever had. I will soon, I just get distracted very easily these days…

Speaking of Patreon, check out Wrestle Me! on there. They recently started their own supporter campaign and as a long-time listener of their show, I thought it only fair to become a patron.

If you also have thoughts on the things discussed here, please feel free to contact me.

Toss a Coin to Your Podcaster

I am a freelance journalist and writer, volunteering my free time because I love digging into stories and because I love podcasting. If you want to help keep The Private Citizen on the air, consider becoming one of my Patreon supporters.

You can also support the show by sending money to  via PayPal, if you prefer.

via PayPal, if you prefer.

This is entirely optional. This show operates under the value-for-value model, meaning I want you to give back only what you feel this show is worth to you. If that comes down to nothing, that’s OK with me, pard. But if you help out, it’s more likely that I’ll be able to keep doing this indefinitely.

Thanks and Credits

I like to credit everyone who’s helped with any aspect of this production and thus became a part of the show.

Aside from the people who have provided feedback and research and are credited as such above, I’m thankful to Raúl Cabezalí, who composed and recorded the show’s theme, a song called Acoustic Routes. I am also thankful to Bytemark, who are providing the hosting for this episode’s audio file.

But above all, I’d like to thank the following people, who have supported this episode through Patreon or PayPal and thus keep this show on the air: Niall Donegan, Michael Mullan-Jensen, Jonathan M. Hethey, Georges Walther, Dave, Kai Siers, Rasheed Alhimianee, Butterbeans, Mark Holland, Steve Hoos, Shelby Cruver, Fadi Mansour, Matt Jelliman, Joe Poser, Vlad, ikn, Dave Umrysh, 1i11g, Vytautas Sadauskas, RikyM, drivezero, Jackie Plage, Jonathan Edwards and Barry Williams.